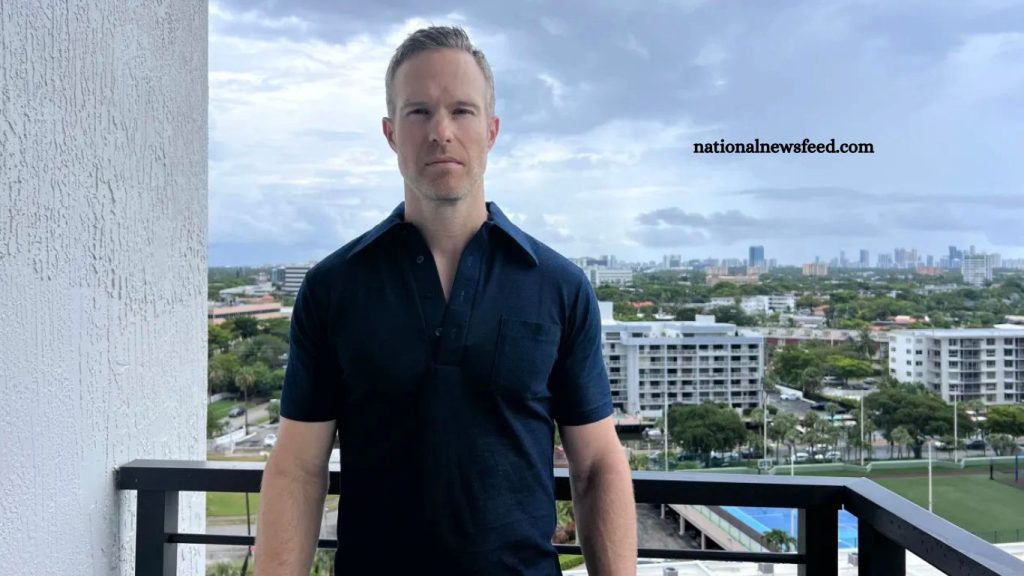

Justin Klish noticed a Yieldstreet ad in February 2022 that immediately grabbed his attention: “Investing Goes like the 1%.” The tagline appealed to his goal of building wealth and diversifying beyond stocks, which were then plummeting. Yieldstreet promises retail investors access to deals once reserved for Wall Street firms and the ultra-rich.

The 46-year-old financial services professional from Miami invested $400,000 in two real estate projects: a luxury apartment building in downtown Nashville backed by former WeWork CEO Adam Neumann’s family office, and a three-building renovation in Chelsea, New York. Both projects targeted annual returns of around 20%.

Three years later, Klish faces devastating losses. Yieldstreet declared the Nashville project a total loss in May, erasing $300,000 of his investment. The Chelsea project now requires fresh capital to avoid a similar collapse. “I lost $400,000 in Yieldstreet,” Klish told CNBC. “I consider myself financially savvy, but I got duped. I worry this will happen to others.”

Distributed Risk

Yieldstreet, founded in 2015, became known for its mission to democratize access to alternative assets such as real estate, litigation finance, and private credit. The platform pools funds from thousands of investors, including Klish, who typically contribute at least $10,000 per project vetted by Yieldstreet managers.

The startup promotes private market investments as a path to higher returns and smoother performance compared with public stocks and bonds. Earlier this month, President Donald Trump signed an executive order supporting private market investments in U.S. retirement plans.

Yet Yieldstreet investors in recent real estate deals report steep losses. Projects often proved far riskier than expected, with funds locked up for years and little return. The company acknowledged that its 2021–2022 real estate offerings were “significantly impacted” by rising interest rates and broader market pressures.

CNBC reviewed dozens of investor letters showing more than $370 million invested in 30 real estate projects, with $78 million already defaulted in the past year. Many investors expect deep or total losses on the remainder. The scope of Yieldstreet’s real estate struggles—its largest investment category—has not been widely reported.

Projects span apartment complexes in Atlanta, Dallas, and Nashville; developments in New York, Boston, and Portland, Oregon; Midwest apartments; and single-family rentals across Florida, Georgia, and North Carolina. Of the 30 reviewed projects, four are total losses, 23 are on a “watchlist” as the company seeks additional capital, and three remain active but have stopped scheduled payouts.

Yieldstreet also shut down a real estate investment trust of six projects last year after its value fell nearly 50%, locking up customer funds for at least two years. Overall real estate returns fell from 9.4% in 2023 to 2% in the company’s latest update. Investor updates are confidential, making it difficult for participants to gauge whether their experience is unique.

Klish grew concerned in early 2023 as updates became delayed and hinted at deteriorating market conditions. Frustrated by a lack of transparency, he turned to Facebook and Reddit forums, discovering dozens of other investors reporting similar losses. “Almost every single deal is in trouble,” he said. In July, Klish filed a complaint with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, alleging that Yieldstreet misled investors; he has yet to receive a response.

Read More: Airline Travel Challenges Intensify This Summer

Missing Ships, Busted Tie-Up

Yieldstreet markets itself as a leading platform for private market investments, a sector that has surged as investors seek yield beyond stocks and bonds. Founded in 2015 by Michael Weisz and Milind Mehere, the company attracted well-known venture capital backers, including Khosla Ventures, Thrive Capital, and General Catalyst. Like fintech startups such as Robinhood and Chime, Yieldstreet embraced a populist message.

“Our mission is to help create financial independence for millions of people by generating consistent, passive income,” Weisz said in a 2020 CNBC interview. Weisz, who became CEO in 2023, has a background in litigation finance, while Mehere, a former software engineer, provided technical expertise. Yieldstreet declined to make the co-founders or other executives available for comment.

In early 2020, Yieldstreet announced a partnership with BlackRock to launch the Prism fund, combining private market assets with conventional bond funds. The move suggested mainstream success, as BlackRock spent 18 months vetting the startup.

The partnership quickly faced setbacks. One Yieldstreet product—loans backed by commercial ships intended for scrap—suffered losses when 13 ships valued at $89 million went missing, according to a 2020 lawsuit against the Dubai-based ship recycler. A British court later ruled in Yieldstreet’s favor. The incident spooked BlackRock, which ended the partnership weeks later.

In 2023, the SEC fined Yieldstreet $1.9 million for selling a $14.5 million marine loan despite red flags about the borrower and failing to use publicly available methods to track the collateral. “YieldStreet aims to unlock alternative investments for retail investors but failed to disclose glaring risks,” an SEC official said.

Despite these challenges, Yieldstreet expanded its platform, emphasizing real estate. By 2023, real estate funds accounted for 26% of investments. The company acquired Cadre, a commercial real estate startup co-founded by Jared Kushner, creating nearly $10 billion in combined investment value.

In May 2025, Yieldstreet replaced Weisz as CEO with Mitch Caplan, former E-Trade chief and board member since 2021. That July, the company raised $77 million in capital, led by Tarsadia Investments.

Difficult News

Yieldstreet expanded its real estate offerings even as market conditions turned sharply against investors. In early 2022, the Federal Reserve launched its most aggressive rate-hiking cycle in decades to combat inflation, dropping the value of multifamily buildings by 19%, according to Green Street’s commercial property index.

Several Yieldstreet-backed projects struggled to meet revenue targets due to price competition, vacancy issues, or rent constraints, falling behind on loan payments. Leveraged investments amplified losses, resulting in complete wipeouts for projects in Nashville, Atlanta, and New York’s Upper West Side. Investor letters show the Upper West Side deal, with $15 million invested, was sold for $1 after all recovery options were exhausted.

It remains unclear if Yieldstreet, which charges roughly 2% in annual management fees, suffered direct losses from these defaults. In 2023 and 2024, the company sought additional funds from investors to rescue troubled deals, marketing these loans as combining debt security with equity upside. In at least one case—the Nashville project—a $3.1 million member rescue loan was entirely wiped out within months.

Yieldstreet told investors, “Following multiple restructuring attempts, the property has been sold … resulting in a complete loss of capital.”

In response to CNBC, Yieldstreet stated it has offered 149 real estate deals since inception and delivered positive returns on 94% of matured investments. That figure likely excludes distressed projects still on its watchlist. The company added that 2021–2022 real estate equity offerings were “significantly impacted by rising interest rates and broader market conditions that pressured multifamily valuations across the industry.”

Adverse Selection

Yieldstreet claims its platform selects only 10% of the deals it reviews, signaling careful risk screening. However, professional investors suggest the startup may be acquiring real estate projects passed over by more established players.

Greg Friedman, CEO of Atlanta-based Peachtree Group, said, “Deals institutions pass on often end up on platforms because retail investors may have less discipline.” He added that Yieldstreet’s post-2022 investments reflected “a lack of discipline in underwriting” amid a higher-rate environment.

In late 2022, Yieldstreet promoted real estate as a “safe(er) haven” during rising rates and inflation, citing the Alterra Apartments in Tucson, Arizona, as an example of a project protected by rent increases and capped interest rates. By 2025, however, the $23 million Tucson deal entered technical default and faced a full write-off, highlighting the risks of relying on perceived market safety.

Mind-Boggling Losses

Customers tell CNBC that Yieldstreet downplayed risks and provided disclosures that were often confusing or misleading.

Mark Underhill, a 57-year-old software engineer, invested $600,000 across 22 Yieldstreet funds and now faces $200,000 in losses on watchlisted projects that never made payouts.

“With any investment, there’s a risk of loss,” Underhill said. “But there’s no consideration of these gut-punch losses. They emphasized collateral and gave reasons to feel protected if a deal went south.”

Underhill, who is recovering from chemotherapy for multiple myeloma, said his losses are forcing him to work beyond his planned retirement. “The thing that is mind-boggling is, how did they fail so badly on so many deals in so many markets?” he added.

Investor documents show that the Upper West Side project was projected to require a 35% drop in sales prices before members would see losses—larger than New York experienced in the 2008 recession. Yet the project defaulted even without such a steep decline.

Similarly, Nashville project investors received letters reporting total losses, while Yieldstreet’s public website initially listed a 0% internal rate of return (IRR), implying full recovery of capital. After CNBC requested clarification, the website was updated to reflect the -100% return.

Quarterly portfolio snapshots also stopped after early 2023, leaving prospective investors largely reliant on the company’s disclosures. Yieldstreet says it updates metrics quarterly, reporting a 7.4% IRR through March 2025—likely excluding the impact of the Nashville defaults disclosed in May 2025.

Mind-Boggling Losses

Customers tell CNBC that Yieldstreet downplayed risks and provided disclosures that were often confusing or misleading.

Mark Underhill, a 57-year-old software engineer, invested $600,000 across 22 Yieldstreet funds and now faces $200,000 in losses on watchlisted projects that never made payouts.

“With any investment, there’s a risk of loss,” Underhill said. “But there’s no consideration of these gut-punch losses. They emphasized collateral and gave reasons to feel protected if a deal went south.”

Underhill, who is recovering from chemotherapy for multiple myeloma, said his losses are forcing him to work beyond his planned retirement. “The thing that is mind-boggling is, how did they fail so badly on so many deals in so many markets?” he added.

Investor documents show that the Upper West Side project was projected to require a 35% drop in sales prices before members would see losses—larger than New York experienced in the 2008 recession. Yet the project defaulted even without such a steep decline.

Similarly, Nashville project investors received letters reporting total losses, while Yieldstreet’s public website initially listed a 0% internal rate of return (IRR), implying full recovery of capital. After CNBC requested clarification, the website was updated to reflect the -100% return.

Quarterly portfolio snapshots also stopped after early 2023, leaving prospective investors largely reliant on the company’s disclosures. Yieldstreet says it updates metrics quarterly, reporting a 7.4% IRR through March 2025 likely excluding the impact of the Nashville defaults disclosed in May 2025.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is Yieldstreet?

Yieldstreet is a fintech platform that offers retail investors access to private market investments, including real estate, marine finance, and private credit. It was founded in 2015 by Michael Weisz and Milind Mehere and backed by major VCs like Khosla Ventures and General Catalyst.

How does Yieldstreet make money?

Yieldstreet charges annual management fees, typically around 2% on invested funds. These fees apply regardless of whether the underlying investments succeed or fail.

What went wrong with Yieldstreet’s marine loan investments?

In 2020, Yieldstreet lost track of 13 ships tied to $89 million in loans. The company later sued the borrower and won in a British court. The SEC also fined Yieldstreet $1.9 million for selling a marine loan backed by potentially stolen proceeds and failing to track the collateral properly.

Why did real estate investments perform poorly?

After the Fed began aggressive rate hikes in 2022, many Yieldstreet-backed real estate projects struggled with higher borrowing costs, low occupancy, and falling valuations. Leveraged projects in cities like Nashville, Atlanta, and New York suffered total losses for investors.

Were investors misled about risks?

Some customers allege Yieldstreet downplayed risks and provided misleading performance data. For example, projects with complete losses were initially listed on the website with a 0% internal rate of return, suggesting investors had recovered their capital.

What is Yieldstreet doing to prevent future losses?

Under CEO Mitch Caplan, Yieldstreet pivoted to a broker-dealer model, offering 70% of funds from established asset managers like Goldman Sachs and Carlyle Group. The firm is shifting from bespoke deals to a more conservative distribution strategy.

Did Yieldstreet recover investor trust after defaults?

Yieldstreet continues to market positive returns claiming 94% of matured real estate investments have delivered gains but some high-profile projects are still on watchlists or in default, leaving investors exposed to losses.

Conclusion

Yieldstreet rose as a fintech innovator promising retail investors access to alternative investments traditionally reserved for institutions. Its early partnerships and rapid growth suggested a bright future. However, the company’s history reveals significant challenges: poorly performing marine loans, real estate projects hit by rising interest rates, and questions about transparency and risk disclosure.